The conference room went silent. Two companies had just spent six months negotiating a $200 million construction contract. Everything seemed perfect. Both sides signed.

Three months into construction, the fights began. The contractor claimed additional work. The client refused payment. Each side pulled out the contract. Each side insisted they were right.

The contract supported both positions. Because it was poorly drafted.

This scenario plays out constantly in construction. Smart people. Good intentions. Terrible contracts.

The problem isn’t a lack of effort. It’s a lack of clarity. Contracts are written in complex legal language that nobody understands. Clauses copied from templates without thinking. Risk allocation that makes no sense for the actual project.

Let me show you how to draft and negotiate contracts that actually work. Contracts that prevent disputes instead of causing them. Contracts where both sides understand their obligations and can execute smoothly.

This isn’t legal theory. This is practical guidance from real projects.

Table of Contents

What Makes a Construction Contract “Strong”?

Strong doesn’t mean aggressive. It doesn’t mean one-sided clauses that favour your position.

Strong means clear. Enforceable. Balanced enough that both parties can live with it.

Here’s what makes a contract strong:

Clear scope. Everyone knows exactly what’s included. What’s excluded? What deliverables are required? No interpretation needed. No ambiguity.

When I read the scope, I should be able to visualise exactly what gets built.

Balanced risk allocation. Risks go to the party best able to control them. Not dumped on one side. Not left ambiguous.

The client doesn’t take contractor performance risks. The contractor doesn’t take risks from client delays. Each bears the risks they can manage.

Enforceable payment terms. Payment follows objective milestones. Timelines are clear. Processes are defined. Security mechanisms protect both sides.

Nobody should wonder when they get paid or how much.

Defined change management. Changes happen. The contract provides a clear process. How to request changes. How to price them. How to approve them. How to implement them.

No informal arrangements. No verbal agreements. Everything documented.

Predictable dispute resolution. When disagreements arise, there’s a clear path. Negotiation first. Escalation steps. Final binding resolution.

Not immediate litigation. But a fair process both sides trust.

Why does clarity beat aggressive drafting? Because aggressive contracts don’t work.

Should all risk be on the contractor? They price it high or cut corners. Include penalty clauses that are clearly unfair? Courts strike them down.

Clarity means both sides understand obligations. Can price risks accurately. Can execute confidently.

That’s a strong contract.

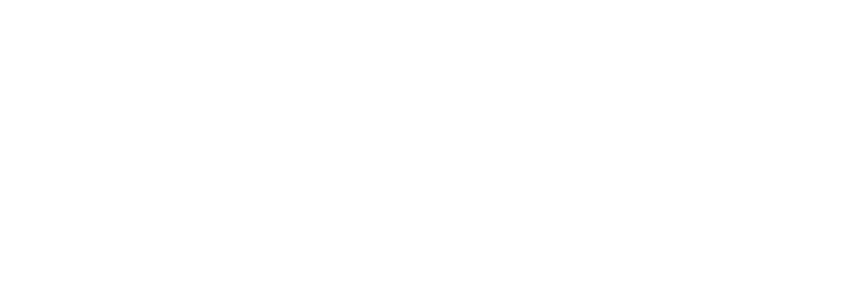

How to Draft Construction Contracts: Step-by-Step Guide

Let me walk through drafting contracts that work.

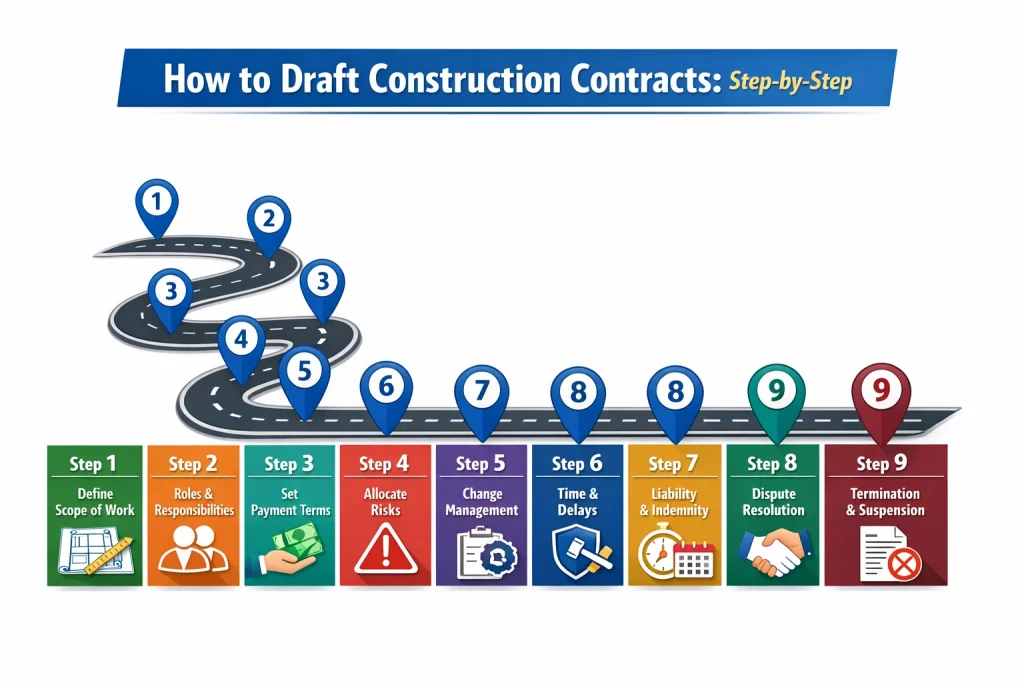

Step 1: Draft a Clear Scope of Work

This is where everything starts. And where most contracts fail.

Vague scope causes more disputes than everything else combined.

The contractor thinks scope means X. The client thinks it means Y. Both believe the contract supports their interpretation. Now you’ve got a dispute that could have been prevented with better drafting.

Use multiple definition methods. Don’t rely on just written descriptions. Use:

Drawings. Architectural drawings. Structural drawings. MEP drawings. Site plans. Detail drawings. These show exactly what gets built.

Reference specific drawing numbers and revisions. “As shown in drawings A101 through A450, revision 3, dated March 15, 2025.”

Specifications. Detailed written specs. Materials. Standards. Quality requirements. Installation methods. Testing procedures.

Be specific. Not “high-quality concrete.” Say “concrete mix design C30/37 complying with BS EN 206, minimum 28-day compressive strength 30 N/mm².”

Bill of Quantities. If using a BOQ, make it detailed. Quantities for every element. Clear descriptions. Units of measurement.

But be careful. In lump-sum contracts, the BOQ can create problems. State explicitly whether BOQ quantities are binding or approximate.

Exclusions and assumptions. What’s NOT included? Be explicit. List exclusions.

“This contract excludes: connection to existing utilities beyond the site boundary, removal of contaminated soil, obtaining environmental permits, and client-furnished equipment.”

Assumptions matter too. What did you assume when pricing? “Scope assumes normal working hours, site accessible 24/7, client provides temporary power and water.”

List your assumptions. If they prove wrong, you have grounds for adjustment.

The test of good scope drafting. Give the contract to an engineer who doesn’t know the project. Can they understand exactly what needs to be built? If not, your scope is unclear.

I once reviewed a contract where the scope said “build a warehouse.” That’s it. No dimensions. No specifications. No drawings referenced. The disputes were inevitable and expensive.

Don’t let that happen to you.

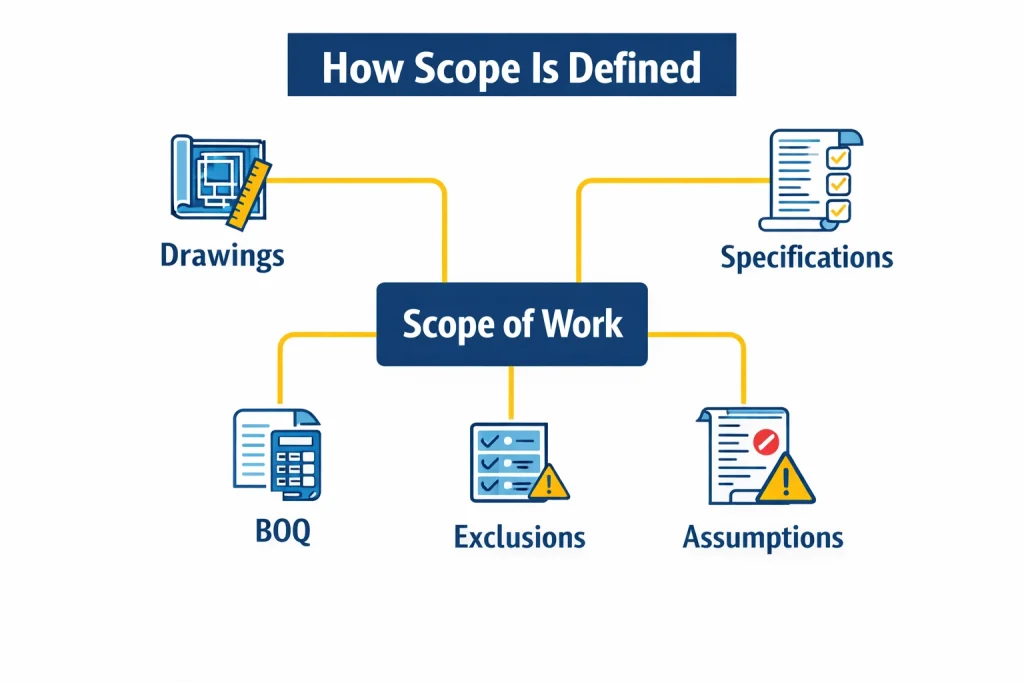

Step 2: Define Roles, Responsibilities and Interfaces

Multiple parties work on construction projects. Each has responsibilities. Define them clearly.

Employer responsibilities. What must the client provide? Site access. Permits. Approvals. Client-furnished equipment. Information. Payments.

State deadlines. “Client shall provide site access by April 1, 2025. Failure to provide access entitles Contractor to extension of time.”

Be specific about information requirements. “Client shall provide soil investigation reports, utility location surveys, and environmental assessments within 14 days of contract signing.”

Contractor responsibilities. What must the contractor do? Design if applicable. Procurement. Construction. Testing. Commissioning. Training. Documentation.

List everything. Include soft deliverables like O&M manuals, as-built drawings, and training materials.

Subcontractor coordination. Most work gets subcontracted. Who manages subcontractors? The main contractor.

State clearly: “Contractor is responsible for the coordination of all subcontractors. Client deals only with Contractor, not with subcontractors.”

Who approves subcontractors? Does the client have veto rights? Spell it out.

Interface risks. Where different scopes meet, problems happen. Define interfaces.

Between the main contractor and separate packages. Between mechanical and electrical systems. Between new construction and existing facilities.

Who coordinates interfaces? Who fixes interface problems? Who pays?

On a refinery project I worked on, the mechanical contractor and instrumentation contractor had overlapping scopes at system boundaries. Neither took responsibility. Equipment sat unconnected for weeks. Cost both time and money.

Clear interface definitions prevent this.

Authority levels. Who can make decisions? Who can approve variations? Who can issue instructions?

Define authority clearly. “Only the Project Manager or persons specifically authorised in writing can issue instructions binding on the Contractor.”

This prevents junior staff from making commitments the client won’t honour.

Step 3: Draft Payment Terms That Actually Work

Payment drives behaviour. Structure it right.

Choose the appropriate payment model. Three main options:

Lump sum. Fixed price for defined scope. Contractor takes quantity risk. Good for well-defined projects. Gives client cost certainty.

Item rate or unit price. Pay per unit of work. Quantity risk stays with the client. Good for uncertain quantities. More flexible but less cost certainty.

Milestone-based. Still lump total. But payment is tied to the completion of defined milestones. Combines certainty with cash flow management.

For most construction projects, milestone-based lump sum works best.

Define payment milestones clearly. Milestones must be objective and verifiable. Not “substantial progress.” Say “foundation concrete for all structures completed and cured, certified by the Engineer.”

Set milestone values. “Milestone 1: Site mobilisation and temporary facilities – 5%. Milestone 2: Substructure complete – 15%. Milestone 3: Superstructure complete – 25%.”

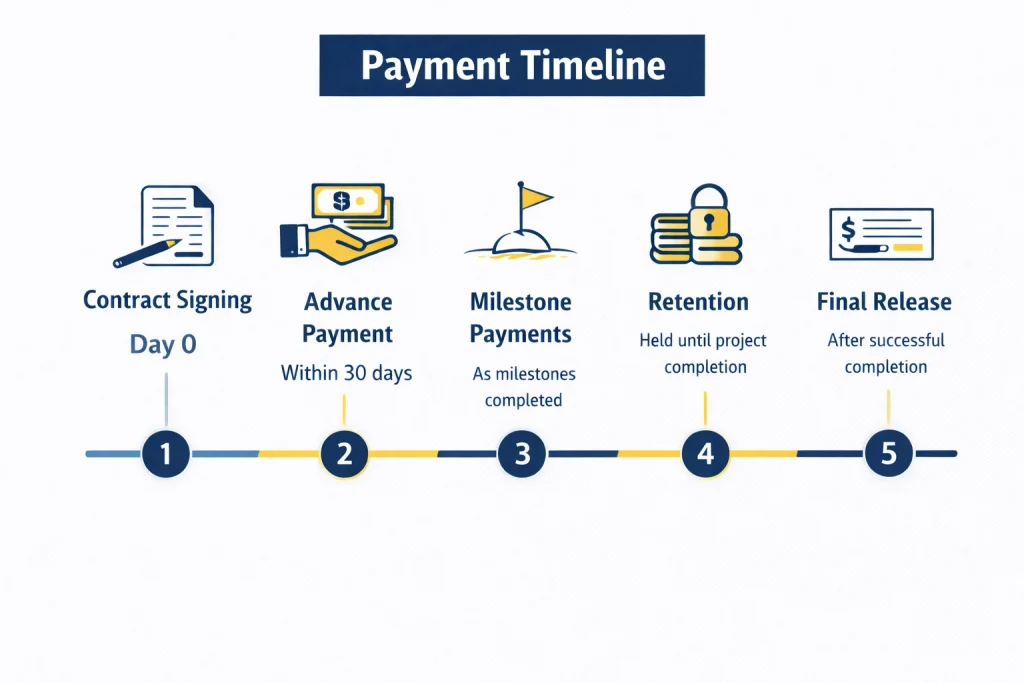

Address advance payments. Many contractors need upfront payment for mobilisation and procurement.

State the advance amount. Usually, 10-20% of the contract value. When it’s paid. Usually, within 30 days of contract signing.

How is it secured? Typically, the contractor provides a bank guarantee for the advance amount.

How is it recovered? Usually, proportional deductions from each payment certificate. “Advance payment shall be recovered at 10% of each interim payment certificate.”

Define retention. Money is held back from each payment. Released after successful completion.

State retention percentage. Usually 5-10%. “10% of each interim payment shall be retained until the Defects Liability Period expires.”

When is retention released? Half at substantial completion. Balance after the defects liability period ends.

Set certification and payment timelines. How often is progress measured? Monthly? Who measures? Who certifies?

“Contractor submits payment application by the 25th of each month. Engineer certifies within 14 days. Client pays within 28 days of certification.”

Clear timelines prevent payment disputes.

Include payment security. What happens if the client doesn’t pay? Options include:

- Right to suspend work after X days of non-payment

- Interest on late payments

- Parent company guarantee if the client is a subsidiary

What happens if the contractor doesn’t perform? Options include:

- Performance bond (typically 10% of contract value)

- Parent company guarantee if contractor is a subsidiary

- Right to terminate for persistent non-performance

Step 4: Risk Allocation in Construction Contracts

Risk allocation determines who bears consequences when things go wrong.

Unclear risk allocation causes disputes. Be explicit.

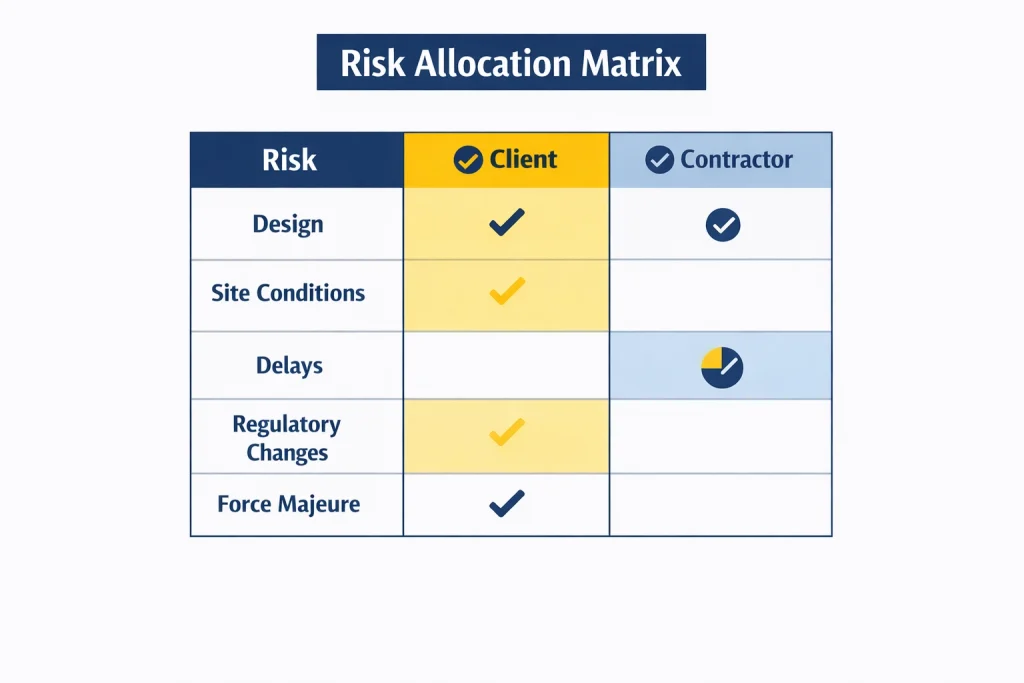

What risk allocation really means. Every project has risks. Design might be wrong. Site conditions might differ. The weather might delay work. Equipment might arrive late. Regulations might change.

The question isn’t whether risks exist. It’s who bears the financial and schedule consequences.

Typical construction risks and how to allocate them:

Design risk. If the employer provides design, they take design risk. If the design is wrong, they pay to fix it. The contractor gets time and cost relief.

If the contractor designs (design-build or EPC), they take design risk. The wrong design is their problem.

State this explicitly. “Contractor is solely responsible for all design and warrants that the design will meet performance requirements.”

Site condition risk. Tricky because site information comes from the client, but the contractor prices based on it.

Balanced approach: Client provides geotechnical investigation. If actual conditions materially differ from the investigation data, the contractor gets relief. If the contractor didn’t properly assess the data, no relief.

“If subsurface conditions differ materially from conditions indicated in the Geotechnical Report dated January 2025, and a competent contractor could not reasonably have anticipated such conditions, Contractor is entitled to extension of time and additional cost.”

Delay risks. Who bears delays from various causes? Split them:

- Client-caused delays: Client bears the cost and time

- Force majeure: Time extension but no cost compensation

- Contractor performance issues: Contractor bears consequences

Regulatory and permit risks. Who obtains permits? Usually split. Major environmental permits are often the client’s responsibility. Construction permits are the contractor’s responsibility.

What if regulations change mid-project? Usually, that’s client risk. “If changes in law after contract date increase costs, Client shall compensate Contractor.”

Force majeure. Events beyond either party’s control. Wars. Earthquakes. Pandemics. Define what qualifies.

Usual consequence: time relief but no money. “Force majeure events entitle Contractor to extension of time but not additional payment.”

Create a risk allocation matrix. Make a table. List risks. State who bears each. Include in your contract as a schedule.

This forces both parties to think through risks during negotiation. Prevents surprises later.

I’ve seen so many disputes where both parties honestly believed the other side had a risk. A simple matrix would have prevented it.

Step 5: Drafting Change Order and Variation Clauses

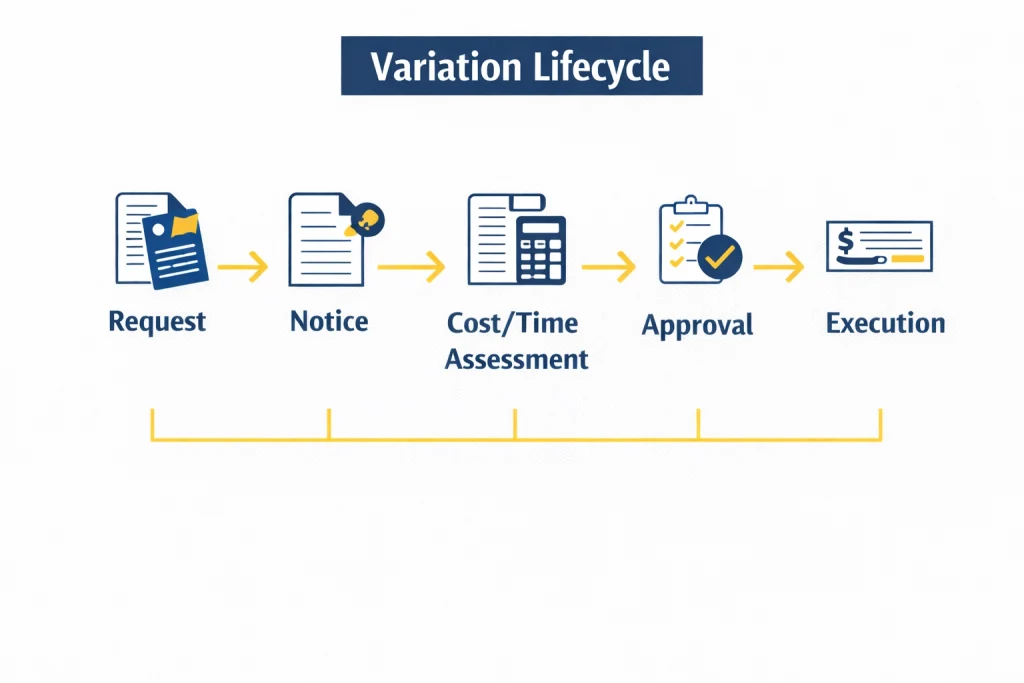

Changes are inevitable. Your contract must handle them.

Define what qualifies as a change. Any deviation from the contract scope. Client requests. Changes due to differing site conditions. Changes from regulatory requirements.

“A Variation is any change to the Works as originally defined in the Contract Documents.”

Establish notice requirements. The contractor must notify promptly when they believe something is a variation.

“Contractor shall give written notice of any claimed Variation within 14 days of the event giving rise to the Variation.”

This prevents surprises. The client learns about potential cost impacts early.

Set out the variation procedure:

- The party requesting the change issues a Variation Request describing the change

- Contractor assesses cost and time impact within 14 days

- Contractor submits a variation proposal with price and time impact

- Client reviews and negotiates if needed

- Both parties sign the Variation Order before work proceeds

Define pricing rules. How are variations priced?

- By mutual agreement as a lump sum

- Using contract rates if applicable

- Using an agreed rate buildup or a schedule of rates

- Cost-plus with agreed percentage markup

- Time and materials as a last resort

State the priority. Try a lump sum first. Fall back to rates. Last resort is cost-plus.

Address time impact. Every variation should include time assessment. Does it delay the critical path? By how much?

“Each Variation Order shall state the adjustment to Contract Price and Completion Date.”

Require authorization. Only authorised people can approve variations. Name them or define authorisation levels.

“Variations under $50,000 may be approved by the Project Manager. Variations over $50,000 require Client Representative approval.”

No work proceeds without signed authorisation. Verbal instructions don’t count.

I worked on a project where the site engineer verbally instructed changes. The contractor did the work. Then submitted bills totalling millions. The client said no authorisation existed. Massive dispute.

Require written authorisation. Always.

Step 6: Drafting Time, Delay and Liquidated Damages Clauses

Time is money. Contracts must address delays clearly.

Define completion requirements. What does “completion” mean? When is the project done?

Don’t say “substantial completion” without defining it. Be specific.

“Completion means: all Works constructed per Contract Documents, all systems tested and commissioned, all punch-list items completed, all required certifications obtained, and Taking-Over Certificate issued.”

Set the completion date. Specific date or number of days after commencement.

“Contractor shall achieve Completion within 500 days of Commencement Date.”

Define the Extension of Time mechanism. Contractors get time relief for delays beyond their control. Define the process.

“Contractor shall give notice of delay within 7 days of the delaying event. Contractor shall submit the EOT claim within 28 days, including an analysis of the critical path impact. The engineer shall determine within 28 days.”

Address concurrent delays. What if contractor delay and client delay happen simultaneously? Who gets relief?

Common approach: If delays are truly concurrent on the critical path, the contractor gets a time extension but not a cost.

“For concurrent delays where both Employer and Contractor risks affect the critical path, Contractor is entitled to extension of time but not the prolongation costs.”

Draft Liquidated Damages carefully. LDs compensate the client for late completion. But they must be genuine pre-estimates of loss. Not penalties.

“If Contractor fails to achieve Completion by the Completion Date, Contractor shall pay Liquidated Damages of $25,000 per day up to a maximum of 10% of Contract Price.”

State the rate. State the cap. Keep both reasonable based on the actual anticipated loss.

Why the cap? Courts can strike down unlimited liability as penalties. Caps make LDs more enforceable.

Step 7: Drafting Indemnity and Liability Clauses

Who pays if something goes wrong? Indemnity and liability clauses answer this.

Types of indemnities. An indemnity is a promise to compensate someone for losses.

Common construction indemnities:

Third-party liability. “Contractor shall indemnify Client against claims by third parties arising from Contractor’s work.”

If the contractor’s work injures someone or damages property, the contractor compensates the client.

Professional indemnity. For design-build contracts. “Contractor shall indemnify Client against losses from design errors or omissions.”

Set liability caps. Unlimited liability makes contracts uninsurable and unpriceable. Set reasonable caps.

“Contractor’s total liability under this Contract shall not exceed 100% of Contract Price, except for: (a) death or personal injury, (b) fraud, (c) willful misconduct.”

The exceptions are important. You can’t cap liability for death/injury or fraud. But operational errors can be capped.

Address consequential damages. These are indirect losses. Lost profits. Loss of business. Reputational damage.

Often excluded. “Neither party shall be liable for indirect, consequential, or special damages, including loss of profit or business interruption.”

Why exclude? Because consequential damages can be enormous and unpredictable. They make projects uninsurable.

Insurance requirements. Require adequate insurance to back indemnities.

“Contractor shall maintain:

- General liability insurance: $10 million per occurrence

- Professional indemnity insurance: $5 million per claim

- Workers’ compensation per statutory requirements”

Require proof of insurance before work starts.

Step 8: Drafting Dispute Resolution Clauses

Despite best efforts, disputes happen. Your contract needs a resolution process.

Multi-tier dispute resolution. Don’t jump to litigation. Use escalating steps.

Tier 1: Project-level negotiation. Project Managers meet and try to resolve. Give them 14 days.

Tier 2: Senior management review. If unresolved, escalate to senior management. Give them 14-21 days.

Tier 3: Mediation. A neutral mediator facilitates negotiation. Non-binding but often effective. 30-60 days.

Tier 4: Adjudication. Quick binding decision by an independent expert. Particularly good for technical disputes. 60-90 days.

Tier 5: Arbitration. Final binding resolution. Expensive and slow but definitive.

State this hierarchy clearly. “The parties shall not commence arbitration until they have attempted resolution through Tiers 1-4.”

Define arbitration rules. Which rules apply? Common options:

- ICC (International Chamber of Commerce)

- LCIA (London Court of International Arbitration)

- SIAC (Singapore International Arbitration Centre)

State the rules. Number of arbitrators. Usually one for smaller disputes, three for larger. Seat of arbitration. Language.

“Disputes shall be finally resolved by arbitration under ICC Rules. Three arbitrators. Seat: London. Language: English.”

Choose governing law. Which country’s law governs? Usually, the project location. But sometimes the client’s home country.

“This Contract is governed by the laws of England and Wales.”

This matters for contract interpretation and enforcement.

Step 9: Drafting Termination and Suspension Clauses

Sometimes contracts must end early. Or work must stop temporarily. Define how.

Termination for default. If one party fails to perform, the other can terminate. Define grounds clearly.

For contractor default: persistent failure to proceed, repeated quality failures, insolvency, abandonment.

“Client may terminate if: (a) Contractor suspends work without right, (b) Contractor becomes insolvent, (c) Contractor fails to remedy breach within 14 days of notice.”

For client default: non-payment, failure to provide site access, or repudiation.

“Contractor may terminate if Client fails to pay undisputed amounts within 60 days of due date.”

Payment on termination for default. The non-defaulting party’s rights.

If the client terminates for contractor default, the client pays for work done minus costs to complete and losses. Often results in the contractor receiving little or nothing.

If the contractor terminates for client default, the contractor gets payment for work done plus a reasonable profit on incomplete work.

Termination for convenience. The client can terminate even without default. But must compensate fairly.

“Client may terminate for convenience upon 30 days’ notice. Client shall pay for work done plus reasonable profit on incomplete work plus costs of demobilisation.”

Contractors don’t like termination for convenience. But clients insist on it. Negotiate the compensation terms carefully.

Suspension rights. Temporary stop to work. Define when it’s allowed and the consequences.

The client can usually suspend for safety, design changes, or other good reasons. Contractor gets time extension and cost reimbursement.

The contractor can suspend for non-payment. “If Client fails to pay within 28 days of due date, Contractor may suspend work upon 7 days’ notice.”

How to Negotiate Construction Contracts Effectively

Drafting is half the battle. Negotiation is the other half.

Change your mindset. Negotiation isn’t about winning clauses. It’s not about forcing the other side to accept your position.

It’s about pricing risk correctly. About finding terms both sides can live with. About creating a contract that enables project success.

An aggressive contract that the contractor can’t accept or must price at ridiculous premiums hasn’t won you anything.

Understand commercial drivers. Why does each party care about specific clauses?

The client wants cost certainty and schedule certainty. They want to minimise surprises. They want single-point accountability.

The contractor wants fair payment terms. They want protection from risks they can’t control. They want clarity so they can price accurately.

Understanding motivations helps find solutions that work for both sides.

Prioritise critical clauses. You can’t fight everything. Pick your battles.

What really matters to your side? Payment terms? Risk allocation for site conditions? Liability caps? Dispute resolution?

Focus negotiation energy on the things that matter. Be flexible on less critical points.

I’ve watched negotiations where one party fought every single clause. Everything became a battle. Exhausting. Eventually, the other side walked away. The project never happened.

Don’t be that party.

Trade risks instead of deleting them. If a risk clause is unreasonable, don’t just delete it. Offer an alternative allocation.

The contractor says the proposed site condition risk is unfair. Don’t just refuse and insist on your position. Offer a compromise.

“If conditions differ materially from the geotechnical report, we’ll share the cost 50/50 up to $2 million, with the client bearing amounts above that.”

Both sides give something. Both sides get protection.

Document negotiated positions. As you negotiate, document agreements.

After each meeting, circulate minutes listing what was agreed. This prevents backtracking later.

Mark up contracts to show agreed changes. Both sides’ initial changes.

By the time you’re ready to sign, there should be no surprises. Everything has been discussed and agreed.

Key Clauses to Focus on During Negotiation

Not all clauses matter equally. Focus on these:

Scope and exclusions. What’s in, what’s out. This drives everything else. Get it clear.

Payment and cash flow. When does money flow? What are milestone values? Advance payment amounts? Retention? Payment timelines?

Contractors live or die on cash flow. Clients want control over payment for leverage.

Find balance.

Risk allocation. Who takes design risk, site risk, delay risk, and regulatory risk?

This has huge pricing implications. Allocate risks to parties best able to control them.

Variations and claims. How are changes handled? What notice is required? How are changes priced?

Poor variation procedures cause endless disputes. Get them right.

Indemnity and liability. What’s the contractor’s maximum exposure? What’s excluded? What insurance backs the indemnities?

Contractors can’t accept unlimited liability. Clients need adequate protection.

Negotiate caps and insurance levels that make sense.

Termination. Under what circumstances can either party terminate? What compensation applies?

This is the escape hatch. Make sure it’s fair but not easily abused.

Construction Contract Negotiation Checklist

Here’s a practical checklist for negotiation:

| Area | Key Questions |

|---|---|

| Scope | Is anything assumed but not explicitly written? Are exclusions clear? |

| Payment | When do I actually get paid? Are milestones objective? Is cash flow manageable? |

| Risk | Who bears delay risk? Site condition risk? Design risk? |

| Changes | How are changes priced? Who approves? What’s the timeline? |

| Liability | What is my maximum exposure? What’s excluded? Is it insurable? |

| Disputes | How fast can disputes be resolved? Is arbitration required before litigation? |

| Termination | Under what grounds can each party terminate? What compensation applies? |

| Insurance | What insurance is required? Are limits adequate? Who pays premiums? |

Work through this checklist for every contract negotiation. It ensures you don’t miss critical points.

Drafting EPC Construction Contract Clauses

EPC contracts have unique characteristics. Standard construction clauses need modification.

Single point responsibility. EPC means one contractor does everything. Design, procurement, construction. This must be crystal clear.

“Contractor is solely responsible for complete design, procurement, construction, testing, and commissioning of the Works.”

Higher risk allocation to the contractor. EPC contractors typically take more risk. Design risk. Performance risk. Often, site risk is too.

Reflect this in your clauses. But ensure the price reflects it.

Performance guarantees. EPC projects often guarantee output or efficiency. The plant must produce X tons per hour at Y efficiency.

“The Plant shall produce a minimum of 500 tons per hour of Product meeting Specification ABC, at a minimum 92% thermal efficiency.”

Define testing procedures. Acceptance criteria. Penalties for shortfall.

“Performance penalty: $50,000 per percentage point below guaranteed efficiency, up to a maximum of $5 million.”

Completion tests. EPC contracts typically require comprehensive testing before takeover. Mechanical completion. Pre-commissioning. Commissioning. Performance tests.

Define each phase. What tests are performed? What results are required? Who witnesses?

Parent company guarantees. For large EPC projects, clients often require guarantees from the contractor’s parent company.

This protects against contractor insolvency. If the contractor fails, the parent must complete or compensate.

FIDIC Contract Drafting and Negotiation

FIDIC contracts are standard forms. But they still require careful drafting and negotiation.

Using standard forms versus bespoke contracts. FIDIC’s advantage is its international recognition. Contractors and lenders know it. There’s established case law.

But standard forms may not fit your project perfectly. That’s where customisation comes in.

FIDIC provides General Conditions. These are standard. Usually not amended.

Special or Particular Conditions customise the contract. This is where you tailor FIDIC to your project.

You can modify risk allocation. Add requirements. Delete provisions. Clarify ambiguities.

Red, Yellow, or Silver Book? Choose based on project type.

Red Book for traditional construction, where the employer designs. Yellow Book for design-build. Silver Book for EPC turnkey.

Match the book to your project delivery method.

Common FIDIC negotiation pressure points:

Employer’s risks in the Red/Yellow Book. These are risks the employer bears. Contractors often want to expand this list. Clients want to limit it.

Time bars. FIDIC 2017 has strict notice requirements. Miss a deadline, and you lose claim rights. Contractors hate these. They negotiate for longer periods or reduce consequences.

Dispute resolution. FIDIC uses Dispute Boards. Some clients prefer direct arbitration. Some contractors want mediation first.

This gets negotiated in Special Conditions.

Liability caps. FIDIC 2017 includes liability cap provisions. The amounts get negotiated. What’s capped? What’s excluded from caps?

Expect serious negotiation here.

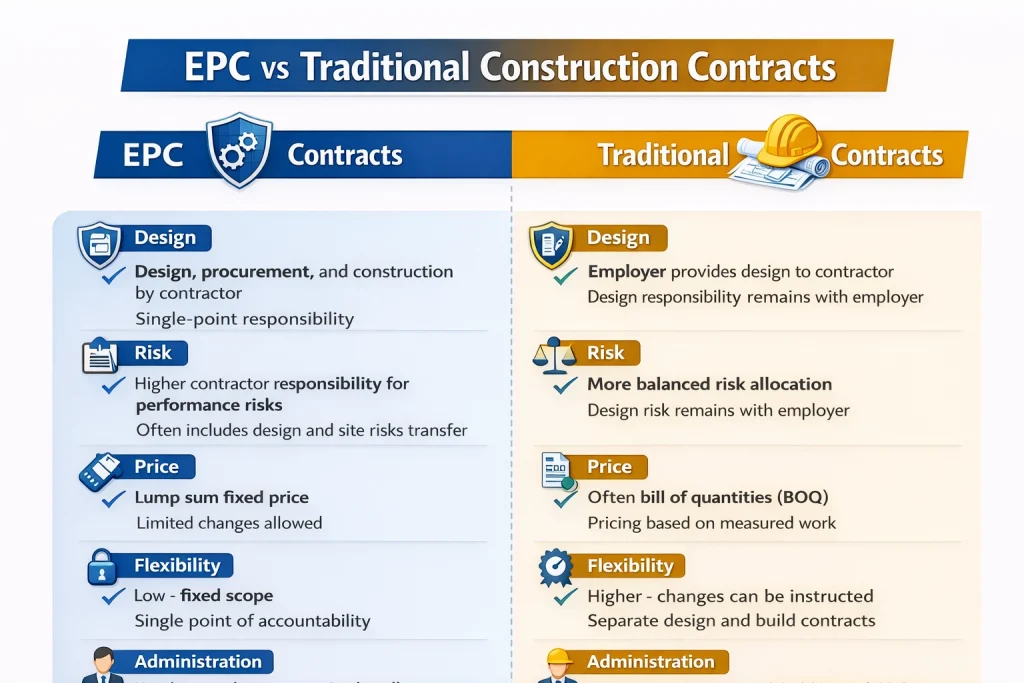

EPC vs Traditional Construction Contracts

Understanding differences helps you choose and draft appropriately.

| Aspect | EPC Contracts | Traditional Construction |

|---|---|---|

| Design | Contractor designs | Employer designs |

| Risk | Contractor-heavy | More balanced/shared |

| Price | Lump sum fixed | Often Bill of Quantities |

| Flexibility | Low – fixed scope | Higher – can adjust scope |

| Completion basis | Performance guarantees | Build per drawings |

| Administration | Employer’s Rep | Independent Engineer |

| Best for | Turnkey delivery, fixed outcome | Employer controls design |

Choose based on your project needs and risk appetite.

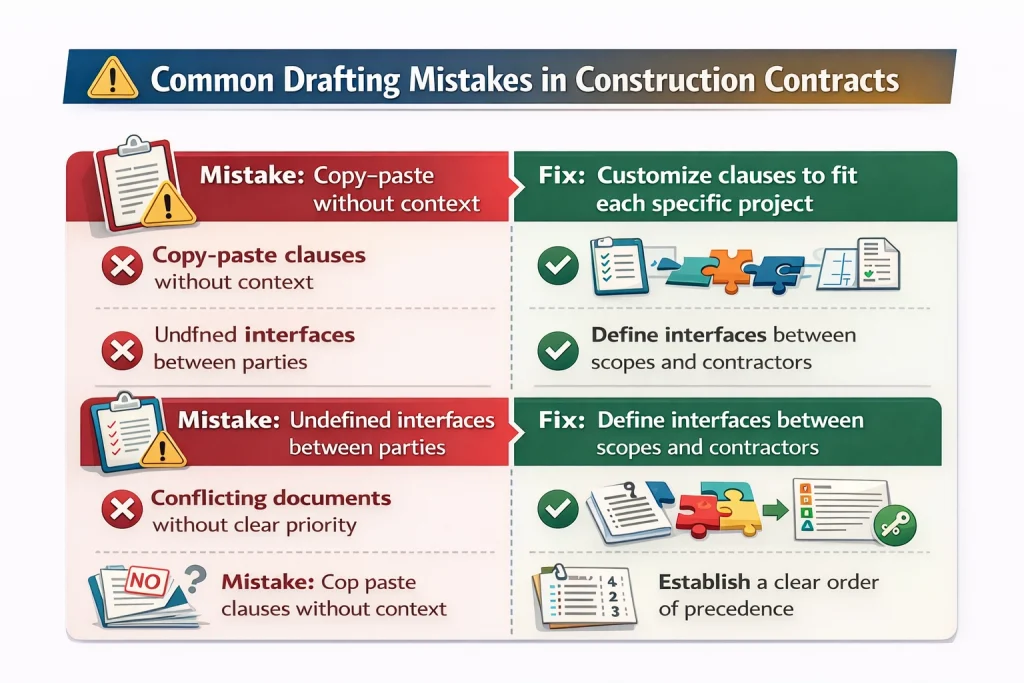

Common Drafting Mistakes in Construction Contracts

Learn from others’ mistakes:

Copy-paste clauses without context. Using standard clauses from other contracts without considering if they fit.

Each project is different. Customise your clauses.

Undefined interfaces. Not clearly defining where one scope ends and another begins.

Always define interfaces explicitly between different contractors or packages.

Missing time bars. Not including deadlines for notices and claims.

Without time bars, claims come years after events. You can’t defend them effectively.

Conflicting documents. Contract documents contradict each other. Priority is unclear.

Always include a priority clause. “In case of conflict: (1) Agreement, (2) Special Conditions, (3) General Conditions, (4) Specifications, (5) Drawings.”

Unenforceable LD clauses. Liquidated damages that are obviously penalties. Courts strike them down.

Keep LDs reasonable. Document how you calculated the rate.

Vague completion definitions. Not clearly defining when the work is done.

Be specific about completion requirements.

Construction Contract Templates and Examples

Templates can help. But use them carefully.

When templates help. They provide structure. They remind you of clauses you need. They save time for standard provisions.

Good starting point for common project types.

When templates fail. When you blindly copy without thinking. When the template doesn’t fit your project. When you don’t customise for specific risks.

Templates are starting points. Not final products.

Every contract needs customisation. No two projects are identical. Different risks. Different parties. Different requirements.

Use templates for structure. But think through every clause. Does it fit your project? Does it address your risks?

Customise accordingly.

Best Practices for Long-Term Contract Success

Good contracts aren’t enough. You need good contract management.

Treat contracts as live documents. Not something you sign and file. Your ongoing reference. Your guide for execution.

Keep it accessible. Team members should know what it says.

Maintain change logs. Track every variation. Date. Description. Status. Cost. Time impact.

This prevents disputes about what was agreed.

Enforce correspondence discipline. All instructions in writing. All agreements confirmed. Meeting minutes circulated within 48 hours.

Build your audit trail as you go.

Align subcontract terms with the main contract. Subcontracts should flow down the main contract obligations. Payment terms. Notice requirements. Liability provisions.

If the main contract has time bars, subcontracts should too.

Train engineers in contract awareness. Engineers often think contracts are someone else’s problem. Wrong.

Technical decisions have contractual consequences. Engineers need basic contract understanding.

Train them. Even brief training helps significantly.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most important clause in a construction contract?

Scope definition. A clear scope prevents most disputes. If everyone understands exactly what’s included and excluded, fewer arguments arise about extra work or non-performance. Scope drives pricing, scheduling, and all other provisions. Without a clear scope, every other clause becomes harder to interpret and enforce. Invest time making the scope crystal clear through drawings, specifications, and explicit exclusions.

How do I protect myself from scope creep in construction contracts?

Define scope precisely with detailed drawings and specifications. List explicit exclusions. Require written variation orders before any additional work proceeds. Include strict change control procedures with pricing and approval requirements. Document everything. If the client requests verbal changes, confirm in writing immediately. Reject informal scope additions. Maintain detailed records of the original scope versus actual work performed to demonstrate changes.

Can aggressive contract terms actually reduce project costs?

No. Aggressive terms increase costs. Contractors price risk into bids. Unreasonable risk allocation means higher prices or contractors walking away. Aggressive liability terms require expensive insurance. Unfair payment terms force contractors to finance projects, costing more. Balanced, clear contracts cost less because contractors price accurately without huge contingencies. Fair contracts attract better contractors and better prices.

Should engineers be involved in contract drafting and negotiation?

Absolutely. Engineers understand technical scope, construction methods, and execution realities. They identify technical risks that lawyers miss. They can assess the feasibility of proposed timelines and specifications. Engineers explain the technical consequences of contract provisions. Best contracts result from collaboration between commercial, legal, and technical professionals. Engineers shouldn’t draft alone, but must participate. Their input prevents impractical provisions.

When should FIDIC contracts be heavily customised versus used as standard?

Use FIDIC more standard when international recognition matters, like projects with foreign lenders or contractors familiar with FIDIC. Customise heavily when the project has unique risks not addressed in standard forms, local law requires specific provisions, or the project delivery method doesn’t match FIDIC assumptions. Balance customisation against losing FIDIC’s established interpretation. Document why you modified clauses.

How can I negotiate fairly without losing commercial advantage?

Focus on fair risk allocation, not winning every clause. Understand the other side’s concerns and address them. Trade concessions strategically. Prioritise your critical terms, but be flexible on others. Build relationships while protecting interests. Fair negotiations create better partnerships, reducing disputes during execution. Contractors price unfair terms highly anyway, so fairness often costs less. Document agreements clearly to prevent backtracking.

What should I do if the other party refuses to negotiate certain contract terms?

Understand why they won’t budge. Is it a deal-breaker risk? Company policy? Past bad experience? Address underlying concerns rather than fighting the clause. Offer alternatives that achieve their goal differently. If truly stuck, quantify the risk and price it separately. Sometimes paying for insurance or guarantees solves it. Know your walk-away point. Some terms are genuinely incompatible with project success.

How detailed should construction contract specifications be?

Detailed enough that a competent contractor knows exactly what to build without guessing. Include materials, standards, quality requirements, installation methods, and testing procedures. Reference international standards where applicable. But avoid over-specification that limits contractor innovation. Strike a balance between clarity and flexibility. For critical elements, be very detailed. For less critical items, performance specs may suffice. Test: Could an engineer build it from your specs?

Should liquidated damages rates be the same for all projects?

No. LDs should reflect actual anticipated losses from delay on each specific project. Consider factors like: lost revenue if delay prevents building operation, ongoing financing costs, market timing losses, or reputation damage. Calculate reasonable estimates. Document your calculation basis. LDs ranging from 0.1% to 1% of contract value per day are common, but